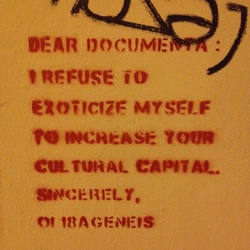

By early summer 2015 it was becoming common knowledge that the big art event documenta was to take place in both Athens and its native Kassel in 2017, and that this was somehow a big deal. Exactly how it was a big deal was unknown and predictions ranged from positive to negative. However, years of crushing political and economic crises combined with uprisings and defeats, fascist wet dreams and waves of refugee influxes had by this point seen Athens move from hot to forgotten a few times. That art and creativity existed in a unique and inspiring way in Athens felt like a well kept secret, far from the mainstream and even invisible to the imagination of many locals who would rather dream of the ghost of Berlin past. Though the conditions are ripe for experimentation and allow for creative infrastructures due to a broader disintegration of economic stability and a solid state, lack of income in the form of art funding and a market also counter the emergence and solidification of art currents. It is very possible to create various kinds of art spaces and live in Greece with a certain form of economic freedom due to the relative low cost of living, but of course this is balanced by the lack of money. This is not a new condition for artists however, as artists tend to be poor and therefore have often congregated in pre-gentrification or pre-development areas, so a location in a limbo of multiple crises fits as an artist habitat. I believe this to be the main reason for an influx of international artists in Athens in the last years, especially young ones, who can have breathing space and contemplate their future moves, a luxury not offered by the expensive capitals of north-western Europe such as Paris, Amsterdam and London. And so it should perhaps not come as such a surprise that documenta appears in Athens, seemingly out of the blue but drawn by those very same conditions that have disappeared in many European capitals. One can also speculate that this old giant of art events came here to gather some kind of relevance as whatever post-WWII rejection and renewal laid at its foundation had long ago become dated, and Kassel as a location feels obsolete. As part of our research, we at the Holobiont Project have often taken up this impending influential art event with artists, academics and other cultural workers both within Greece and internationally, in order to try to understand it but also to gather impressions and expectations. Our findings have almost been entirely negative, with expectations being expressed through terms such as exploitation, exoticisation and colonialism, painting a picture of a massive art market monster invading Athens, feeding itself on voluntary work and subsidies for the benefit of a few strong art powers whilst giving nothing back but empty hope. It has been suggested that looking at the aftermath of documenta might be more interesting than speculating about the event itself, as a retrospective perspective would allow for clearer analysis of the real impact.  An early insight into these feelings was well represented by a stencil that we first spotted at the walls of Circuits and Currents, a space run by students from the Athens School of Fine Arts and a product of a cooperation with the Academy of Fine Art in Munich. The stencil said: “DEAR DOCUMENTA: I REFUSE TO EXOTISIZE MYSELF TO INCREASE YOUR CULTURAL CAPITAL. SINCERELY, OI I8AGENEIS”. The translation of the signature means The Indigenous. More than a year later documenta had established itself more thoroughly and after the opening of an office in the historically important Polytechnic University in Exarchia, Athens, and several smaller talks and presentations, the more significant 34 Exercises of Freedom began in September 2016 in a building at Parko Eleftheria (Park of Freedom). The events that started to take place there, and are still ongoing, opened up a multitude of themes and infused both international and local perspectives into a forum for art theory and issues about representation. The inclusive and diverse nature of these talks offers a surprising countering of the initial expectations of documenta that we gathered from a broad range of discussions. This seems to indicate that the documenta team are not entirely cut out from the local reality and critical voices, and that the theme of this specific edition of documenta, ‘Learning from Athens’, is more than a phrase but rather an actual approach. Interestingly, the mentioned stencil which appeared against documenta was used for this very programme, as the letters were digitalised and applied as the heading for the events, showing an awareness of critique but also a full willingness to unashamedly borrow, or steal, thereby capturing and/or recuperating criticism in order to control it. The second round of this programme saw an event take place on the 26th of October entitled ‘Introduction to the Society of the Indigenous’ which referred specifically to the stencil and its signature. In the presentation of the theme it was explained that the stencil had indeed been noticed and that the signature, The Indigenous, had been of specific interest to the documenta working group as they would themselves like to speak to the indigenous. Rather than to seek out the blessing of some vague Greek identity however, the talk on this specific day used the term indigenous to question national identity. The description read as a list of checkpoints of a funding application:

“By establishing the notion of ithageneia (the Greek word for "indigenous") as a condition, The Apatride Society tries to go beyond a Eurocentric perspective, while encouraging the observation of the shifting forms and territories of contemporary colonialities and new imperatives in the production of global and local subjectivities. The Apatride Society aspires to become a forum for debate, addressing how political Otherness (including the conditions of migration, precarity, dispossession, and statelessness as well as political, racial and sexual minorities) can be articulated today through occupations, resistance, and acts of citizenship.” A major part of the talk consisted of personal stories being told by the specific segment of Greek society which is caught in the limbo of statelessness due to Greek laws of nationality. Greece has a surprisingly nazi-style definition of nationality which is based on blood right, also generally known as jus sanguinis, which means that migrants can find it impossible to become citizens no matter how long they reside in the country or even if they would be born there. People born of Greek parents outside of Greece can still become citizens even without ever having lived there, thereby being able to vote, travel freely within the European union and enjoy all the perks of citizenship. Despite challenges to this legal framework, it is currently the case that many 1st, 2nd and 3rd generation immigrants in Greece live without the same rights as Greeks due to the impossibility of receiving citizenship. As a part of looking at The Indigenous, this talk allowed for the telling of some of these perspectives as several people presented their situations and their various struggles to organise and challenge this current reality. One participant who has lived in Greece for 30 years described how both her child and grandchild were born in the country but were practically stateless, not able to vote or exist as citizens. Similar stories followed and participants were allowed to represent themselves rather than be spoken about, as academics, politician and activists complemented their stories with further information. This perspective is an interesting spin on the topic of indigenous. By problematising its meaning the documenta working group managed not to answer the criticism portrayed in the stencil, but at the same time they challenge concepts of national identity and allowed for the presentation of a largely unknown perspective. Furthermore, by promoting the voices of established migrant groups in Greece, they bypassed the trend seeking characteristic of much of the art world, which has seen a massive focus on recent migration as desired topic. This trend seeking approach might be best signified by the art of Ai Weiwei which has attracted much attention in recent years, both positive and negative, as he spent time in Greece and created various conscience raising works in Berlin. In our interactions with international artists in Greece, the topic of the refugees has come up several times as a topic of interest to somehow be captured, as if it is a way to gain relevance. The long term Greek migrant reality is an original and underrepresented subject matter which can be portrayed with more long term analysis and through a multitude of experiences, as was the case at this specific event. Other talks have covered a multitude of topics such as indigenous rights, sexuality, war, pornography, violence, torture, history, dictatorship, LGBTQ representations, anarcho-feminism, capitalism, gender and democracy with visitors and contributors from around the world and locally. The forum has allowed for the infusion of a wide range of ideas and has provided insights for locals and visitors alike. Whatever one may think about the actual events, the diversity is difficult to dismiss as uninteresting. These Exercises of Freedom have provided something to the local artistic and cultural milieu, and beyond it, in a way which goes against initial assumed criticisms that were directed against documenta. This does not mean that a critical approach towards documenta is now unnecessary, but it may be time to consider that presumptions are precisely presumptions, and that positive things might very well be born from this major art event which seems likely to frame art and culture more generally in Athens, and Greece, in the near future. It may also be a good time to consider what exactly we expect from the established art world. It is often discussed in terms of themes, meanings and representation with cross-academic influences and bounder pushing approaches. This might be a part of it, and very much a part which belongs in art schools and art theory but these themes are often the flavours used to spice art in its more capitalist form, the art market. In many ways art is a commodity, to be collected by mostly rich people or to be used to acquire funding or prestige. The criticism levelled towards documenta hides this larger problematic, art is a product that needs to adhere to market demands and the industry often uses exploitative tactics such as free labour or shallow trend seeking approaches in order to maximise value and profit. That documenta is a part of that larger art world is true, but the target is missed by focusing on this particular event’s presumed failures without recognising that they are characteristics of the larger art world.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHolobiont Production Team Archives

August 2019

Categories |

HOLOBIONT noun ho·lo·bi·ont (ˈhō-lə-bī-ŏnt) |

Website by Black Button Studio

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed